The State of Black Characters in Comics

Motivation

When I was a little Indian-American kid, I always loved watching action-packed Bollywood movies with my family. At the time, I thought it was mostly because they starred powerful heroes and heroines doing super cool stuff. A little older now, I realize that while this was true, it was crucial that these heroes and heroines looked like me. I realize now that there was something subconscious in my head that said: “This guy looks like me and he’s doing some pretty noble and heroic stuff right now, so I must be capable of that same stuff”.

And I’d argue this is true for all kids while growing up. They can watch all the shows and movies, read all the books, have all the best teachers, but the moment they see someone who looks like them doing amazing things, all of a sudden it clicks. The reality clicks that: “Hold on, maybe I can be great too.”

As it is currently Black History Month and the long awaited superhero movie, Black Panther, just came out, I thought it would be a perfect time to look at the historic representation of black characters in an increasingly popular media: comics. Given that the Silver Age of Comics pretty much coincided with the Civil Rights Era in America, I thought it would be really interesting to see how diversity changed in the comics during and outside this time.

Let’s dive in!

The Data

For this project, I scraped all the data from online wiki pages using the Python web scraping library called BeautifulSoup. It is important to note that the process of reading data from a webpage and putting it into a spreadsheet isn’t always clean cut and there are bound to be some errors in the final data.

Just to point out one known source of error, comic books constantly write and rewrite characters as well as pass on the mantle of one superhero/supervillain to another character. Sometimes, a hero will originally be written as white and many decades later will be rewritten as black, for example. When scraping the wiki page for that character, it is possible that the original publication date will be fetched instead of the rewriting date. All this is to say, note that there will be minor errors although I have tried my best to maintain the accuracy of the scraped data. Whew! Warning over.

I scraped the following wiki pages for this project:

- List of Black Superheroes

- List of Black Supervillains

- List of Marvel Comics Characters

- List of DC Comics Characters

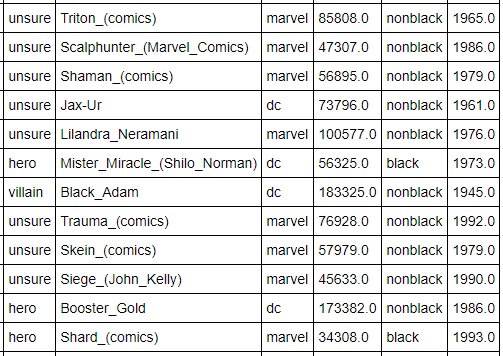

In the end, I produced a dataset with the following six columns: Alignment (Hero, Villain, or Unsure), Character Name, Comic (Marvel or DC), Length of Wiki Page, Black or Nonblack, Year When Introduced. A snapshot of the data is shown below.

Let’s ask some questions and see the answers to them!

How Has Racial Diversity in Comics Changed Through Time?

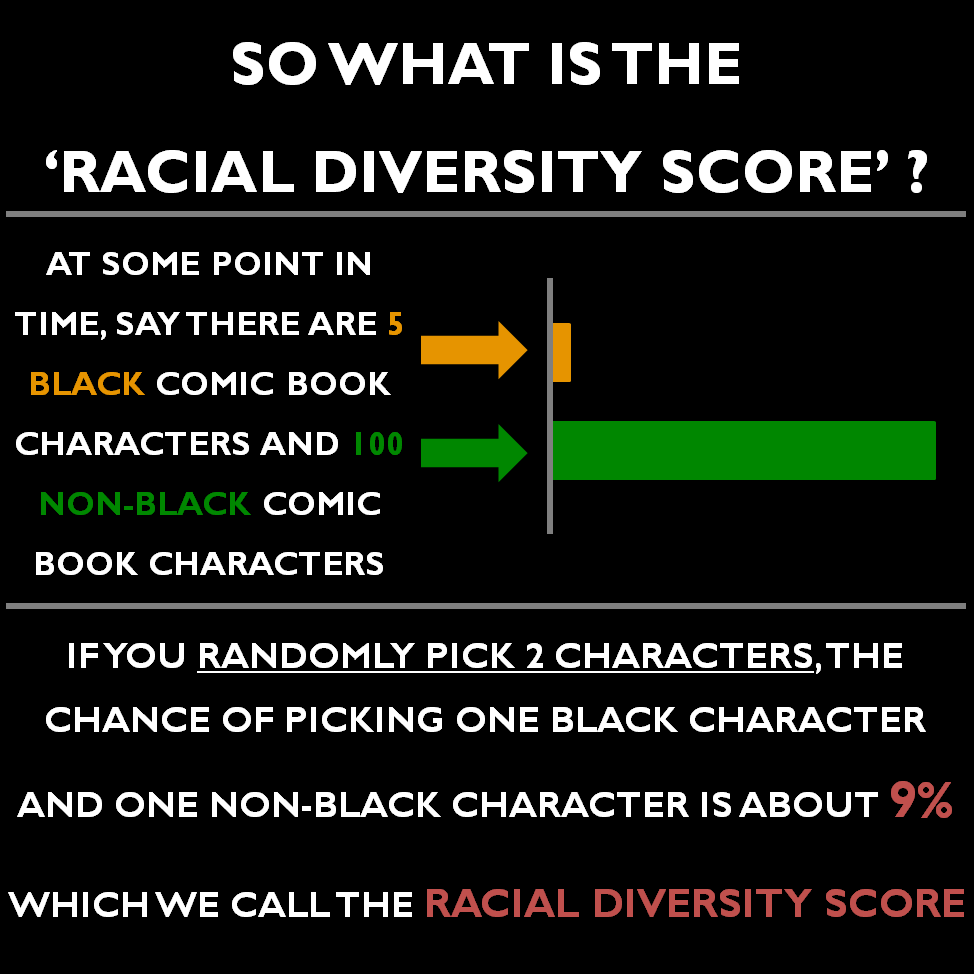

Since we are focusing on black characters here, we will define something called the racial diversity score as shown below:

Now that we know what the racial diversity score is, let’s see how it has changed through time.

Key Points:

-

We see that the diversity score starts at 0 while Marvel and DC did not have any black characters. Then, upon the addition of their respective first black characters, the score initially spikes and then gradually falls since it likely was not a plan to continue regularly introducing black characters in the 1950’s.

-

Interestingly, we see that in the period from about 1965-1978 there is a rapid growth in the diversity score for both Marvel and DC. It happens to be that this period immediately followed and somewhat intersected with the Civil Rights Era in the U.S., which spanned from about 1954-1968.

-

Since 1980, the diversity score has still been growing, which is a good sign, but at a much slower rate than in the aforementioned boom period. Looking at the graph, we see that the diversity score went from about 2% to 7% (5% rise) in the 14 years we mentioned before but since then, it has only gone up about 3% in the last 40 years.

-

Another feature of this graph is that the lines for Marvel and DC intersect quite often, which we can read as a good sign since neither publisher seems to be consistently outperforming the other in terms of writing black comic book characters. Still, it is worth noting that in the boom period (1965-1978), Marvel had a steeper growth in diversity score than did DC. And, in the modern era, DC seems to have a slight lead in diversity score over Marvel.

-

If the proportion of black characters in comics were the same as actual black people in the US, 13%, the diversity score should be around 0.23. Seeing as it is currently just over 0.1, we still have some work to do if we aim to represent our populace fairly in the comics.

How about we take a quick look at some of the key black comic characters which made that period from 1965-1978 so prosperous.

Are Black Characters Represented as Heroes or Villains?

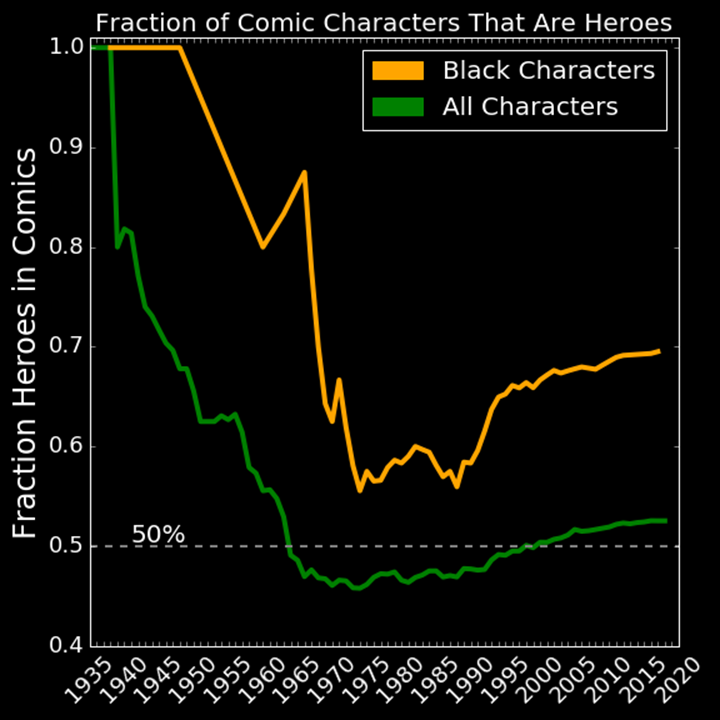

Now that we have analyzed the rate at which black characters have been added to comics over time, a deeper question would be whether these characters are usually the good guys or the bad guys. Let’s look at a time series of what percent of characters are heroes for black and all comic book characters.

Key Points:

-

The most striking thing about this chart is that the line for black heroes is always above the line for all heroes. This means that black characters are represented as heroes at a consistently higher rate than for comic characters in general. This seems to be a good sign.

-

We also see that the line for black heroes is always above 50%, meaning that so far, half of all black comic book characters have always been heroes. We see this is not true for all comic book heroes. From about 1960 to 1995, the line for all heroes dipped below 50% meaning that during that time period, most comic book characters were either villains or neither (some characters are more ambiguous than either heroes or villains or I just wasn’t able to tell by scraping the wiki pages).

-

A possible explanation for the decline in the hero rate for both series until about 1990 might be because most major comic book heroes have a whole gallery of bad guys. For every Spider Man, there are 15-20 solid bad guys.

Let’s lastly look at how many days, on average, readers need to wait for a new black character vs a new non-black character.

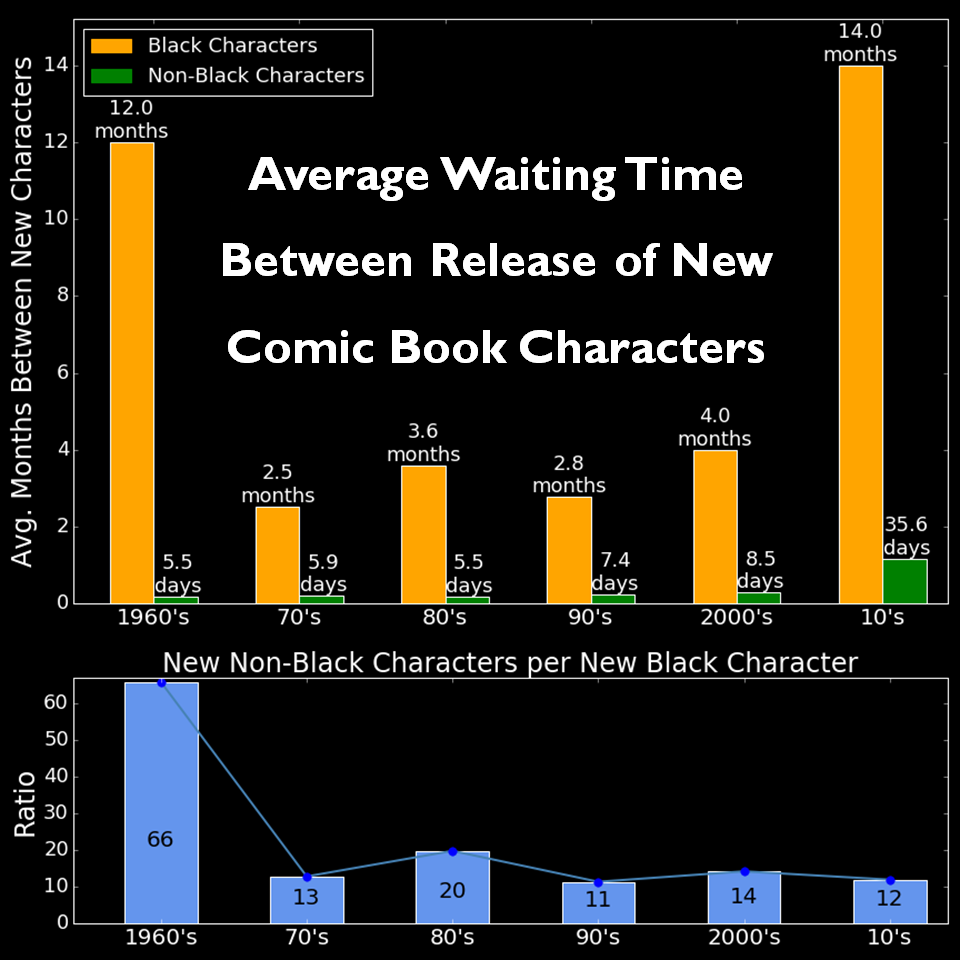

Waiting Time for New Black Characters vs New Non-Black Characters

Key Points:

-

Right away, we see that the average wait time for a black character is much more than the average wait time for a non-black character across all time periods. We are more interested in how the ratio of the wait time for a black vs. nonblack character changes over time. The ratio, shown in the bottom plot, starts very high, at 66. This means that in the 1960’s there were on average 66 new nonblack characters for every new black character in comics.

-

We see that this ratio gets a lot better in the coming decades and is now around 12, meaning that there are on average 12 nonblack characters for each black character. Based on the current U.S. population demographics, we would expect this ratio to ideally be about 7 new nonblack characters per new black character.

-

When I saw this plot, I was trying to explain the sudden spike in wait times in the 2010’s for both black and nonblack characters. My two guesses are either that in recent years the focus has been on comic book films rather than movies (although I don’t have a good enough grasp on comic books to know if this is true), or that there is simply a lag time between characters appearing in comics and their wiki pages being created (I think more likely).

Wrapping Up

So what do we take away from all this? Well our optimistic pieces of good news are that racial diversity in comic books has only been increasing since about 1965, black characters have by and large been written as heroes in the comics at a higher rate than characters overall, and that increasingly more black characters have been written per new nonblack characters.

Still, in all of the metrics that we analyzed, the reality still does not match up to the ideal case if black characters were represented at a proportional rate to what we would expect based on the U.S. population. So, there is clearly work to be done.

In addition, there are many dynamics relating to comic books and racial diversity that we did not measure. In recent years, we have had many rewritings of existing comic book characters as people of color. This spans even from the 1970’s where readers got a black Green Lantern to recent years where readers got an Afro-Latino Spider Man (2011) and a Korean-American Hulk (2015).

These are undoubtedly huge steps towards a more diverse comic book universe, but I would personally argue that it means so much more when people of color are written directly into a completely new comic book character rather than assigned to a comic book character originally written for a white male, such as the examples just given. The creative license and depth of story that can be incorporated into the stories of icons like Black Panther or Storm just cannot be matched when there is a pressure to fit a person of color into a decades-old mold.

Still, we need to applaud and support racial diversity in comics in any way it may manifest, especially with an increasing number of film and TV adaptations. We need to show the diverse youth in this country that people like them are incredible.

Thanks for reading and please leave comments below!