Why Girls Belong in STEM and Why There is More to the Picture

Quick Links:

- Motivation

- The Data

- Reason #1: Girls are More Likely to Leave Courses than Boys Given the Same Grades

- Reason #2: Girls Develop More Aptitude from Course to Course

- Reason #3: Girls Retake Courses at a Much Lower Rate

- Reason #4: Girls Are Able to Recover Their GPA Better than Boys

- Why We Must Look Deeper Than ‘Girls vs. Boys’

- Conclusions

Motivation

The subject of gender inequalities in Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics (STEM) fields has been a hot and controversial topic for many, many years. Traditionally, these fields were reserved for males, with the populace thinking females were either uninterested or inherently unskilled to pursue them. In the modern era, even though there has been progress in the U.S. workforce for women, this progress has not been universal. For example, although women make up now 48% of the U.S. workforce, they comprise only 24% of all STEM workers, with males making up the other 76%. Some believe that this is not a failure of society and rather recall the arguments of the past stating that women are not adept at these fields explaining their low representation. Others believe strongly that girls are better suited to STEM fields than boys, using only simple GPA comparisons as evidence. This author aims to dig deeper not through qualitative methods but rather by using a much finer data-backed lens to look at the exact places where girls excel in STEM fields.

The Data

This data comes from the UCLA Department of Mathematics. This author, while an undergraduate student in the mathematics department there, used this data for a wide variety of projects. The dataset contains ~300,000 rows, each of which represents an instance of a particular student taking a particular course in a particular term. There is also information about the student’s gender, major, and self-reported ethnicity. The dataset spans the years 2000 through 2015. It is important to note that any term when a student took a course in the mathematics department, this dataset would capture information about all other courses the students was enrolled in as well.

Reason #1: Girls are More Likely to Leave Courses than Boys Given the Same Grades

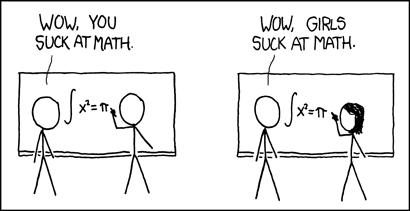

Let’s jump right in! One argument which aims to explain girls dropping our of STEM fields is that they are ‘just not good at them’. Believers of this statement believe that girls are not as adept at STEM fields as boys and so get lower grades, prompting them to drop out. This author chose to analyze this statement for the two biggest introductory mathematics courses at UCLA and most other undergraduate universities: Single Variable Calculus and Multivariable Calculus.

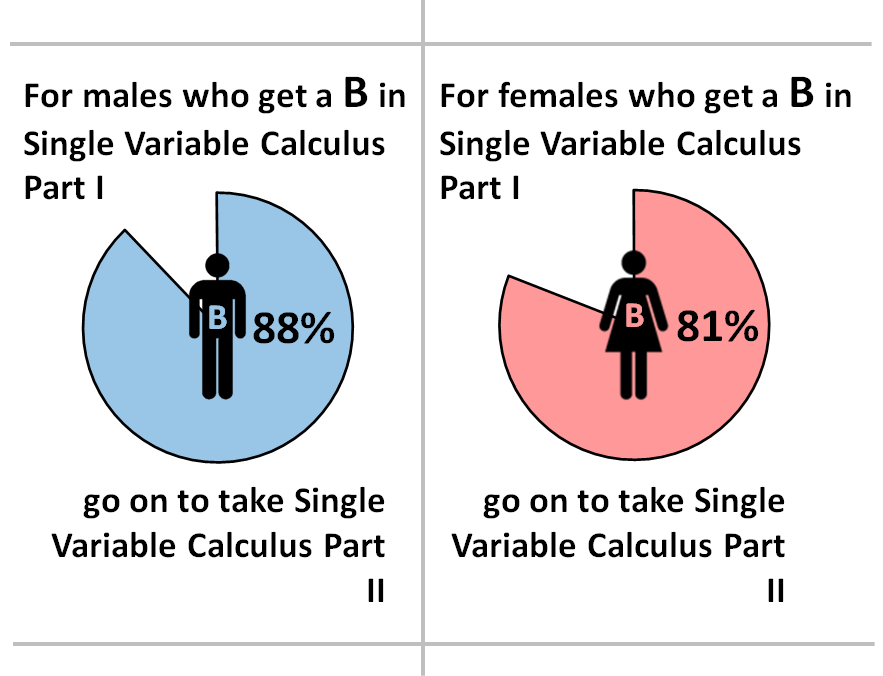

At UCLA, which operates under the quarter system, each of these courses is split into a Part I and Part II, which are to be taken in that order. In order to ensure that the students we consider are required to take both parts of both courses, we consider for now only students in majors which are required to do so, such as Mathematics, Engineering, etc.

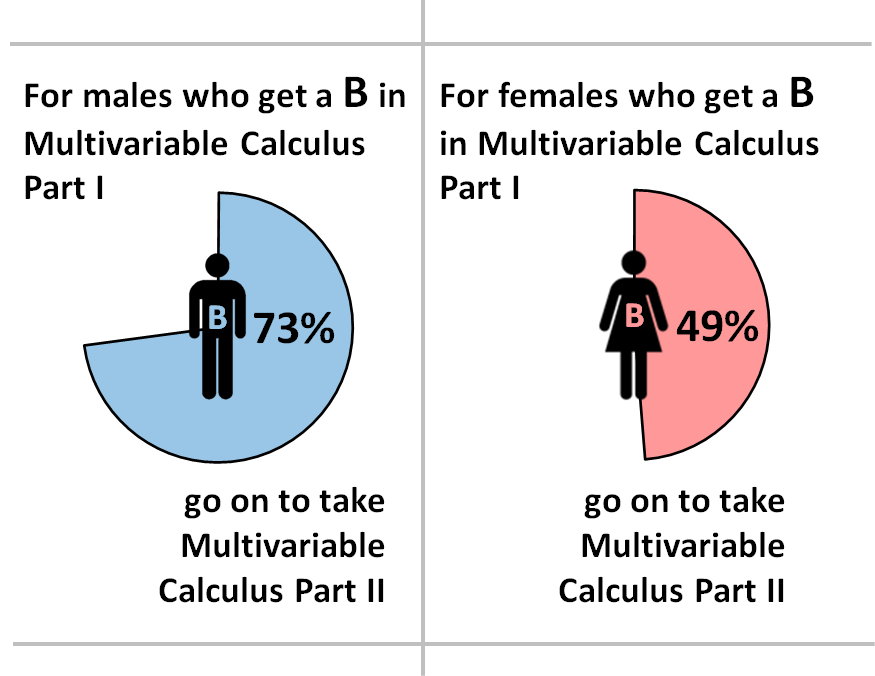

We also choose to only consider those students who got a grade of a B-, B, or B+ in the first part of each of our two courses. These are students who, for the most part, mastered the course material, but might have missed some concepts here and there. If continuing on to the second part of the course were based on grade alone, then we would expect boys and girls who got B’s in the first part to move on at nearly equal rates, right? The figures below show the reality of the situation.

As we see, in Single Variable Calculus, there is already a 7% difference, in favor of boys, for continuing to take the second part of this course. If we don’t consider this a big difference, we only need to look at Multivariable Calculus where this is now a stark 24% difference in favor of boys, with less than half of all girls moving on to take the second part of the course.

There has to be more than just grades driving whether students drop out of STEM courses or not. We really must ask ourselves what a B represents to a boy vs. a girl in a STEM field. Do they interpret this grade differently? Is it a sign of accomplishment for one while being a sign of underperformance for the other? Although these questions lie outside the realm of data science, they are worth asking if we are to figure out why girls, performing at the exact same level as boys, are more inclined to discontinue their STEM courses.

Reason #2: Girls Develop More Aptitude from Course to Course

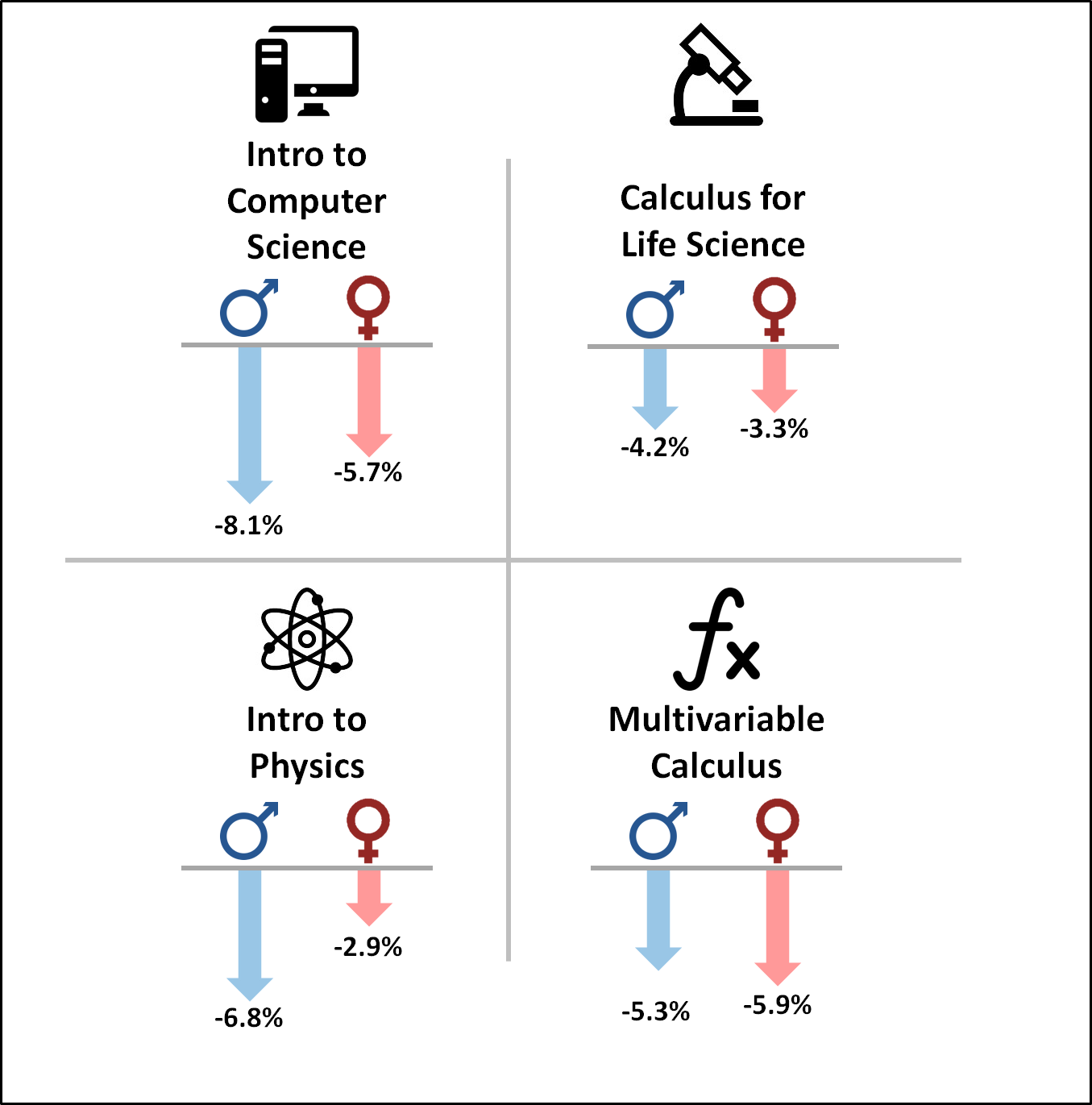

It is no mystery that as students progress in a course sequence, the courses get tougher and tougher. It should also then come as little surprise that students’ grades tend to drop thoughout a course sequence. Yes, they get better at the course material, but not fast enough (especially on that hyper-rapid quarter system) to keep up with the difficulty of that next course. Let us ask then the question of whose grades suffer more: boys or girls?. We choose to look at four of the most important introductory course sequences at UCLA: Introduction to Computer Science, Physics, Calculus for Life Sciences, and Multivariable Calculus. These courses are taken primarily by students in their first and second years at UCLA. The figure below shows the average drop in grade as students progress from the first part of each course to the second.

We see that for three of the four courses, girls’ grades drop by much less than do boys’. Without falling into the correlation vs. causation trap, we can brainstorm what this might imply. It is perhaps indicative of girls retaining more knowledge from one course to the next, or of honing their skills during course sequences.

We see that the final course, Multivariable Calculus, shows the opposite story with girls’ grade loss being higher than that of boys’, but the difference is not nearly as stark as in the first three courses considered. As some additional evidence of courses not pictured, girls’ grades also drop by less in the course sequences for: Calculus for Life sciences, Single Variable Calculus, and Probability Theory.

Reason #3: Girls Retake Courses at a Much Lower Rate

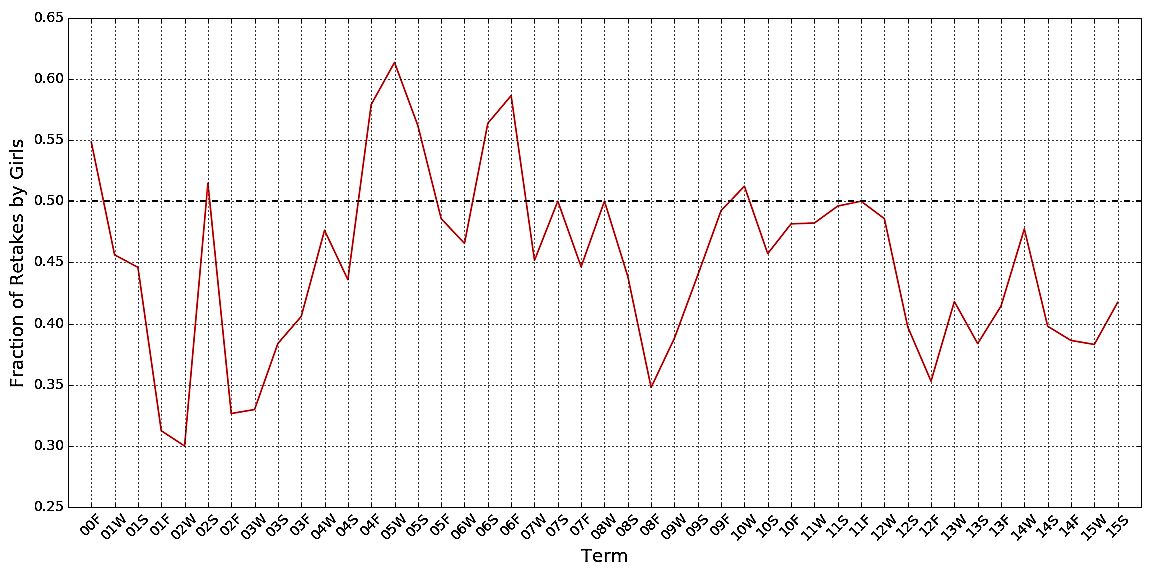

We all know that many students are required to retake courses due to not getting a passing grade. This can be due to a wide variety of factors and is ultimately beneficial for the student in terms of ultimate success. It can be helpful to analyze whether boys or girls retake courses at a higher rate. The answer will hopefully be indicative of how adept each group is at getting passing grades in STEM courses and continuing on through their majors. In order to have a comparison of only STEM students we consider only students from STEM majors. The results appear in the figure below.

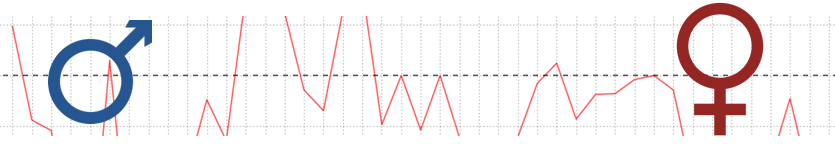

Wow! The red line shows fraction of retakes due to girls for each term from 2000 through 2015. We see that save for a select few terms, this line is always under 50%, indicating that girls make up fewer (often much fewer) of the retakes in a given quarter than do boys. And yes, this does account for the differences in relative proportions of boys and girls in STEM courses each quarter.

Interestingly, in the most recent five years of the data (2010-2015) the line is always below 50%, indicating a possible time trend. Either way, our results show that girls are more capable of continuing on in their STEM course sequences unimpeded than boys generally are.

Reason #4: Girls Are Able to Recover Their GPA Better than Boys

There is a big angle which we have not even considered yet and which is often the bane of all students’ existence: saving your GPA once it takes a bad hit. Many students have been there. You’re going about your coursework and then you hit one quarter where things just do not go your way. Whether it is academic burnout, a set of impossible courses, or increased commitment to work, your GPA takes a noticeable hit. And with GPA, it takes a long while to recover from a hit.

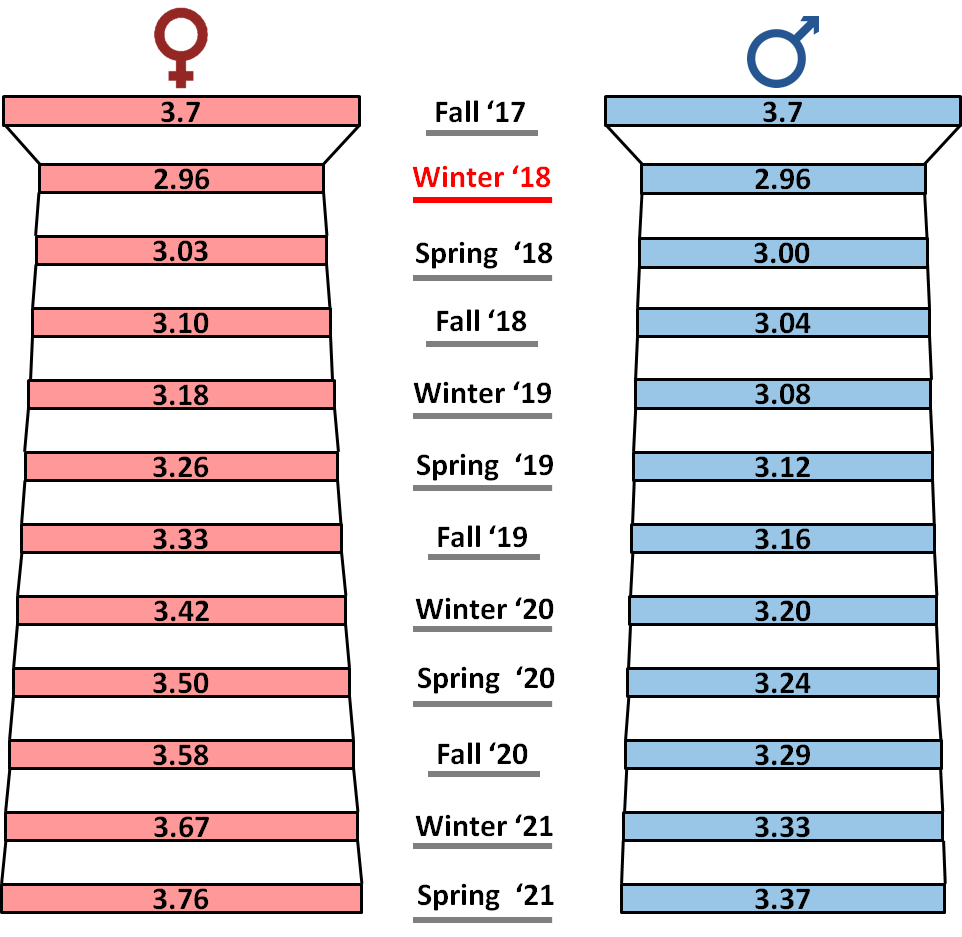

We thus want to know, among students whose GPA took a bad hit, are girls or boys better able to recover from that hit in the long run? We will define a ‘bad hit’ as a drop in GPA of 20% or more. Note that this is like having your GPA go from 3.7 to 2.96 or from 3.0 to 2.4 in just one quarter. We measure the ability of a student to recover by taking their GPA just after the hit and comparing it to their GPA in their final quarter in the dataset.

To make things more concreate, suppose that you take a GPA hit from 3.0 to 2.4. Suppose after 9 quarters you graduate and your GPA is at 2.75. To raise your GPA from 2.4 to 2.75 over 9 quarters, you averaged a GPA growth of 1.52% per quarter. We complete this calculation over all students who took at GPA hit and split up the results into boys and girls. We keep our calculation to be over STEM majors again.

We find that, on average, boys recover their GPA at a rate of 1.3% per quarter and girls at 2.4% per quarter. Doesn’t seem like a big difference? Well, let’s see what this difference builds up to over time. Suppose we have a boy and a girl in STEM. Suppose they both receive a 3.7 GPA after their first quarter and then take a 20% GPA hit their second quarter and are down to a 2.96 GPA. We then let their GPAs grow at the respective male/female growth rates and observe the results.

We see quite a difference! We see that for the boy, after 10 quarters, at the point of his graduation, he has raised his GPA to only 3.37, not close to the 3.7 it once was. For the girl on the other hand, she has raised her GPA to 3.76, exceeding her GPA before the hit. Although these 1.3% and 2.4% may not seem very different, they compound over time to create sizeable results. We thus see that girls are much more able to conduct ‘damage control’ of their GPAs if and when a GPA hit occurs than are boys, on average.

Why We Must Look Deeper Than ‘Girls vs. Boys’

Some of you might be tired by now of this ‘Girls vs. Boys’ dialogue. In truth, there is much more to the story. Indeed when we focus on girls vs. boys as a whole, we forget that there are even more diverse sub-groups within ‘girls’ and ‘boys’: those determined by ethnic background. While it may be true that girls perform better on some academic metric than boys, we need to ask whether this is true for all girls or just select groups. Here we will just scratch the surface.

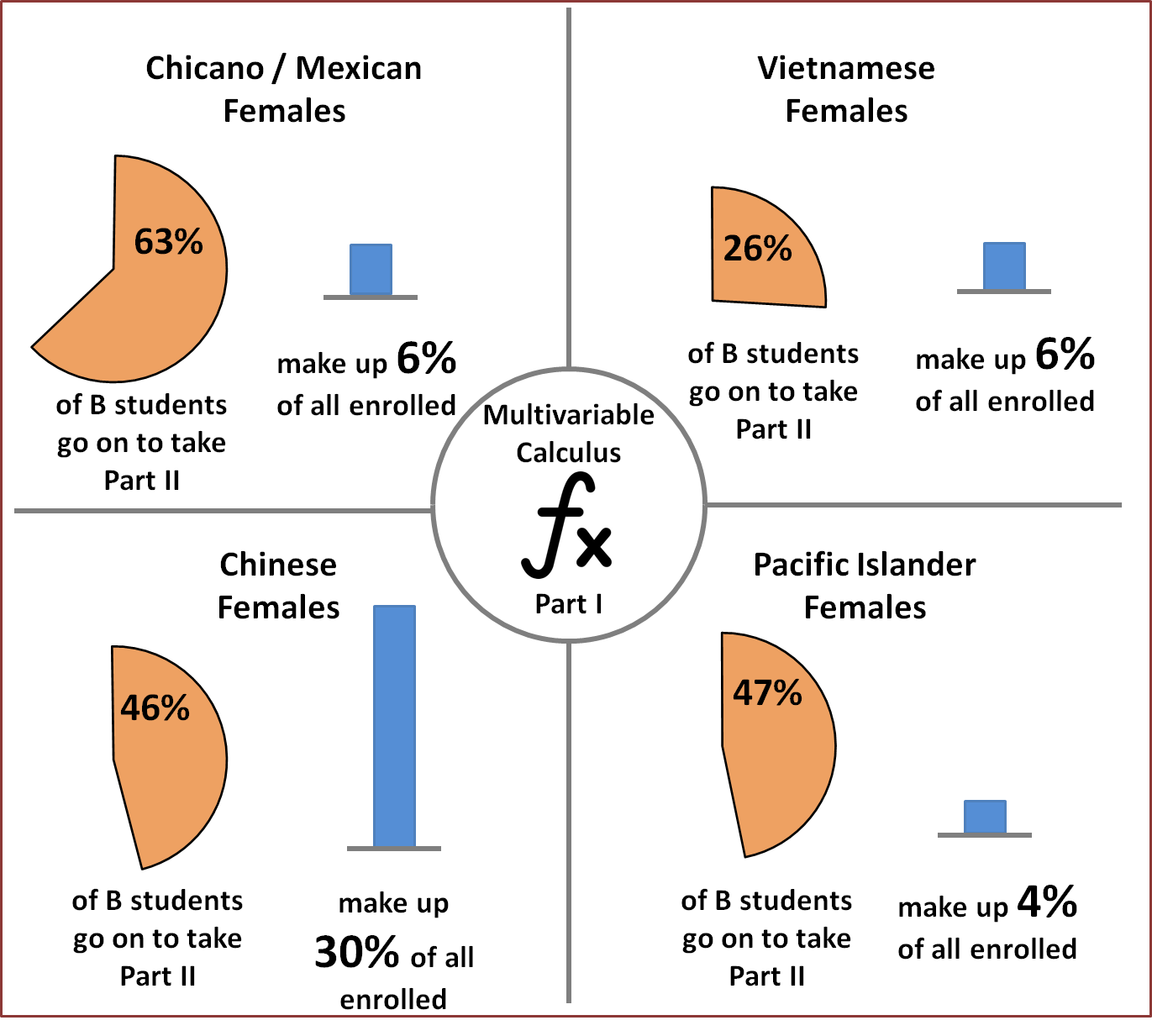

In a case-study like fashion, we will focus our attention to girls taking Multivariable Calculus and conduct a similar analysis to earlier in this post. We will look at four ethnic groups: Chicano/Mexican, Vietnamese, Chinese, and Pacific Islander, and analyze the proportion of girls in each ethnic group that move on to the second part of the course given a B grade in the first part. We also compare this with each ethnic group’s representation in the course. We see the results below.

There is a lot of information here so let’s break it down. Looking first just at the top row, at Chicano/Mexican females and Vietnamese females, we see that they make up the same proportion of students in the course, 6%, but have starkly different rates of transfer to the second half of the course.

In contrast, looking now at the bottom row, we see that Chinese females and Pacific Islander females make up a very different proportion of enrolled students, and yet have nearly identical rates of transfer to the second half of the course. Many of you surely have a bunch of “why?” questions about this data and in all honestly, this author does as well.

Are there cultural differences in these considered ethnic groups that hold a B grade to vastly different standards? If you are a student in one of these ethnic groups, does it affect your retention if you see more or fewer people in your ethnic group in the lecture hall? This, author, being in none of these mentioned ethnic groups, is not really sure of the answers here but would love to hear any discussion in the comments below!

Conclusions

After all, this post used data from one public university among the many, many universities out there. And that does not even include any data about K-12 schools, where student aptitudes for STEM fields really start to blossom. Still, it is worthwhile to drive the ‘Gender Differences in STEM’ narrative away from just asking “who gets better grades?” into much richer, more nuanced considerations such as those considered in this post.

Because in the end, if we are using school performance as a proxy to success in life, grades are not even close to all that matters. It matters also how much you can improve from course to course. It matters also how you can recover from a really bad quarter. It matters also how you feel when you get a B in a course versus how the person next to you feels, and why those differences in feelings occur whether it is due to gender, ethnicity, or one of the many other factors of identity not considered here.

If we, as a society, are really hoping to become experts in ‘Gender Differences in STEM’, we must first understand this subject on a much deeper, data-backed, level by conducting more and broader analyses.

Thanks for reading and please leave comments!