How Many Hearts Beat in Sync With Yours?

The idea of two hearts beating in unison has long been a powerful image in poetry, music, and romance. Let us see what the realm of mathematics has to say about this idea. The question we will answer is a natural one, but one which will require careful analysis:

On average, how many hearts beat in sync with yours?

Of course, our first question should be:

What does it mean for two hearts to beat in sync?

We will define two basic notions in answering this question.

Heart rate: The number of times a heart beats per minute measured in beats per minute (BPM)

Offset: Given that two hearts share a heart rate, the time delay between their beats measured in seconds

Thus, we say that two hearts beat in sync if they have the same heart rate and same offset.

We will be using a half-empirical, half-theoretical approach to answering our question about how many hearts beat with yours.

First the statistics!

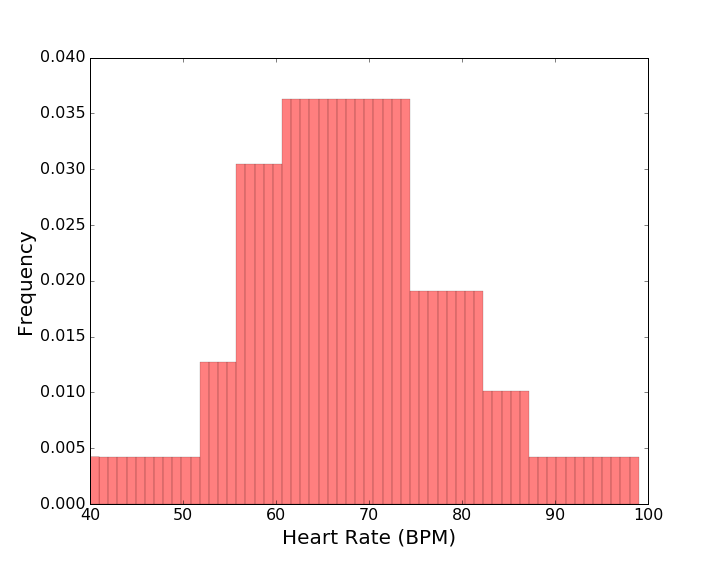

From Statistics Canada, Canada’s National Statistics Agency, we gather data on the distribution of resting heart rates for people ages 6 to 79. This data gives the 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th and 95th percentile for resting heart rate.

Since we wish to have finer grained data, we will need to make an assumption here.

Assumption 1: The distribution of heart rates between the provided percentiles is uniformly distributed.

This assumption is surely not fully correct but it will serve us well in the absence of finer grained data. We will also assume that our minimum resting heart rate is 40 BPM and the maximum is 99 BPM. These numbers come from an article about normal heart rates.

Given our assumption so far, we can generate a histogram of the heart rates.

Time for some math!

First we’ll define

\[S = \textrm{Number of people whose heart beats in sync with yours}\]If we index each person in the world as $i=1,2,3 … , N$ where you are person $i=N$, then we can define

\[B_{i} = \textrm{A variable which is 1 if person i's heart beats in sync with yours and 0 if not}\]What we are after is the mean of $S$, also called the expected value of $S$ and denoted as $\mathbf{E}(S)$. Note that

\[S = B_{1} + B_{2} + ... + B_{N-1} = \sum_{n=1}^{N-1} B_{i}\]Why? Well $S$ is the number of people in the world whose hearts beat with yours and $B_{i}$ is 1 if and only if person i’s heart beats in sync with yours. So, summing up all the $B_{i}$’s we will get exactly the count of how many people whose hearts are in sync with yours.

So we want:

\[\mathbf{E}(S) = \mathbf{E}(\sum_{n=1}^{N-1} B_{i}) = \sum_{n=1}^{N-1} \mathbf{E}(B_{i}) = \sum_{n=1}^{N-1} \mathbf{P}(B_{i}=1)\]using in the second equality that the expected value of a sum is the sum of the expected values and in the last equality the fact that the mean of an indicator variable is the probability that this variable is 1.

We can go one step further if we make another assumption:

Assumption 2: Heart rates are independent between people.

This is likely much easier to swallow than Assumption 1 but of course is still not completely true as people who work out together, attend the same sporting event, etc. will have more similar heart rates. Still, on a global level, we should be safe with this assumption.

Then, our independence assumption allows us to reduce the result to:

\[\mathbf{E}(S) = \sum_{n=1}^{N-1} \mathbf{P}(B_{i}=1) = (N-1) \times \mathbf{P}(B_{i}=1)\]so that we need only to find $\mathbf{P}(B_{i}=1)$.

Exiting the math-o-sphere for a moment, we only need to find the probability that someone’s heart is in sync with yours.

Now, under what conditions would someone’s heart be in sync with yours? As noted earlier, we need only that both your heart rates are the same and your offsets are the same. For example, both your heart rates could be 55 BPM and you have the same offset, or perhaps your heart rates are 77 BPM and you have the same offset, or perhaps you both share a heart rate of 90 BPM with the same offset.

In fact, there are infinitely many heart rates that you can share! How do we simplify this? Well, we will make another assumption here.

Assumption 3: We will treat the continuous range of heart rates as a range of integer values.

That is, if we are considering heart rates between 40 BPM and 52 BPM, we choose to split this interval up into 12 allowable integer heartbeats. Why do we do this? Looking at the way heart rate is typically reported by medical equipment, it is given in integer valued beats per minute.

Now, given that two people have the same heart rate, how do we measure whether they have the same offset?

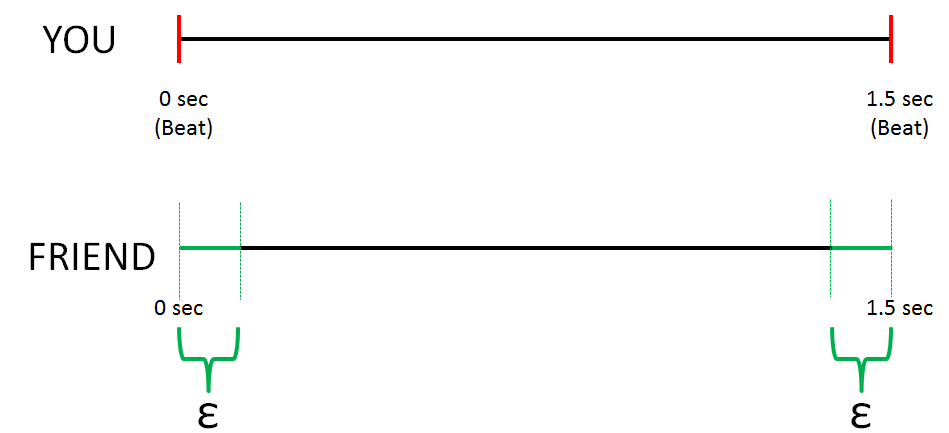

Let’s think about this with an example. Say both you and your friend have a heart rate of 40 BPM which is the same as 40 beats per 60 seconds which implies that your hearts beat once every 1.5 seconds.

Now, the probability that your friend’s heart beats exactly when yours does is 0 because there are infinitely many possible offsets in a finite amount of time. Thus, we will need to make a final assumption in order to conduct a meaningful analysis going forward.

Assumption 4: Two hearts with the same heart rate will be considered as having the same offset if their beats are within some error tolerance of one another.

Essentially, if your friend’s heart beats just a tiny fraction of a second before or after yours does, we will consider the offsets to be the same. We will denote the error tolerance as $\varepsilon$. Going back to our 40 BPM example, we allow that your friend’s heart beats in any of the green regions in the figure below. Note that the probability that your friend’s heart beats in the green region is $\frac{2\varepsilon}{1.5}$ since we have an allowable range of $2\varepsilon$ in a total range of $1.5$.

So, if two hearts beat at $K$ Beats per Minute, they each beat once every $\frac{60}{K}$ seconds and the probability that they have the same offset is $\frac{2\varepsilon}{\frac{60}{K}} = \frac{K\varepsilon}{30}$.

We will let $\varepsilon$ be 1% of $\frac{60}{K}$ going forward which implies that the probability that two hearts with the same heart rate share an offset is $\frac{0.01 \times K \times \frac{60}{K}}{30} = 0.02$ regardless of the heart rate.

Now, we are ready to finish our calculation!

Recall that we are looking for $\mathbf{P}(B_{i}=1)$, the probability that someone’s heart beats in sync with yours.

Note that:

\[\mathbf{P}(B_{i}=1) = \sum_{i=40}^{99} \mathbf{P}(\textrm{Your Heart Rate = i and Their Heart Rate = i and Offsets match})\] \[= \sum_{i=40}^{99} \mathbf{P}(\textrm{Your Heart Rate = i}) \times \mathbf{P}(\textrm{Their Heart Rate = i}) \times \mathbf{P}(\textrm{Offsets Match})\] \[= \sum_{i=40}^{99} \mathbf{P}(\textrm{Heart Rate = i})^2 \times \mathbf{P}(\textrm{Offsets Match}) = 0.02\times\sum_{i=40}^{99} \mathbf{P}(\textrm{Heart Rate = i})^2\]by the independence assumption between two people’s heart rates and the fact that the probability of a matching offset is always 0.02.

Now, finding the probability that a heart beats with heart rate $i$ is as simple as taking the percentile range that the heart rate falls into and dividing by the number of integers in that percentile range.

To be more clear suppose we are trying to find $\mathbf{P}(Heart Rate = 85)$. We note that 85 BPM falls into the 83-88 BPM range, which contains 5 integer values and comprises 5% of the total range of heart rates.

Thus, using our Assumption 1 about uniform distribution, $\mathbf{P}(Heart Rate = 85) = \frac{0.05}{5} = 0.01$ (We can also just read this 0.01 as the height of the 85 BPM bar in our histogram above). We use the same procedure with all other heart rates.

After doing all appropriate calculations, we end up with:

\[\mathbf{P}(B_{i}=1) = 0.00053\]That is, the probability that your heart beats in sync with another heart is 0.053%, very small indeed.

Using the fact that the current world population is around 7.5 billion,

\[\mathbf{E}(S) = (N-1) \times \mathbf{P}(B_{i}=1) = (N-1) \times 0.00053 = (7500000000 - 1) \times 0.00053 = 4006696\]So, under our four assumptions, the expected number hearts that beat in sync with yours is around:

Wow!

In the interest of transparency, let us see what happens to this 4 million if we relax each of our four assumptions.

To relax Assumption 1, we would need to find finer grained data than we do now. Given the true distribution of heart rates between the given percentiles, our estimate of 4 million may rise or fall.

Assumption 2 may be the most difficult to relax since we would need some underlying model of how one person’s heart rate affects that of others in the world, an extremely challenging task. This also has an indeterminate effect on our final result.

If we relax Assumption 3, we will no longer treat heart rates as only being able to take integer values but rather consider them to take continuous values in the range 40 to 100. This will cause our final result of how many hearts beat with yours to be driven to 0.

Why would that be? Well, without even going into the calculations, if we allow any real valued heart rate between 40 and 100, the probability that your heart rate exactly matches someone else’s is very very slim, actually it’s 0. It’s a consequence of the fact that there are an infinite amount of heart rates to choose from, something that isn’t true with discrete integer values.

Last, if we relax Assumption 4, essentially forcing $\varepsilon$ to be 0, we will also drive the final result to 0. This is basically the same reason as for Assumption 3: two offsets being exactly the same is a probability 0 event.

Note also that our final result is quite dependent on the choice of $\varepsilon$. That is, if we let $\varepsilon$ be 2% of $\frac{60}{K}$, then the probability that two hearts with the same heart rate share an offset is $\frac{0.02 \times K \times \frac{60}{K}}{30} = 0.04$, which will eventually double our 4 million to around 8 million.

Finally note that there are some implicit assumptions that were made such as that the Canadian population’s heart beats are representative of those in the whole world and that we consider those outside the range 6 to 79 to have the same distribution of heart rates as those in that range.

The latter of these is definitely not true since those outside the range are young children and elderly people, but again, this assumption serves us well in the absence of the appropriate data.

All that said, the above analysis, complete with its assumptions, is an interesting way to think about how many of us around the world are walking around with our tickers pounding in rhythm.

Thanks for reading and please leave comments!