Building an Efficient Job Shift Scheduler

Quick Links:

- Motivation and Background

- The Current System

- What are the Variables?

- Rules for Scheduling

- Picking the Best of the Best

- Varying Shift Types

- Looking Back to Optimize Forward

- Let’s See Some Results

- So How Fast Is It?

- How Do I Use It?

Motivation and Background

I currently work as a Resident Assistant (RA) at my university. My responsibilities include organizing engaging and fun events for residents who live on my floor, serving as an academic and emotional resource for these students, and completing nighttime work shifts, which RAs call “duties”, on a rotating basis. These duties are divided into two types, ON duties and IN duties.

If I am assigned to an ON duty on a given night, I am responsible for patrolling various floors of my building multiple times, ensuring that students are not violating housing policies, and checking for maintenance issues. These ON duties last from 7PM until 7AM during which time I can be contacted at any time to respond to anything from an innocuous noise complaint to an unconscious resident who needs immediate medical attention. From my experience, these shifts can be taxing and too many of them in a short time frame can impact sleep patterns, alertness, and even academic performance.

On the other hand, if I am assigned to an IN shift on a given night, I am not responsible for patrolling any part of the building and will only be contacted to respond to an incident if all the people with ON shifts that night are busy dealing with incidents.

The number of people scheduled for ON and IN shifts each night varies with the size of the particular building. Larger buildings have three ON duties and three IN duties per night with smaller ones having fewer of each type of shift.

Furthermore the particular number of the ON shift makes a difference. For example, in my building the shifts are designated ON 1, ON 2, and ON 3 and are responsible for patrolling, among other areas, the lobby, the basement, and the courtyard, respectively. It is apparent that during the winter, it is much more preferable for RAs to patrol indoors than outdoors.

The Current System

These ON and IN shifts are not randomly assigned. Every three to four weeks, RAs fill out preferences for the coming weeks about which days they would prefer to have an ON shift, which days they would prefer to have an IN shift, which days they cannot have any shift (perhaps because they have other plans that night), and which days they are indifferent about getting assigned a shift.

Once these preferences are recorded, a team of two or three RAs attempts to create a harmonious schedule which balances the workload for each RA, ensures ample time between ON shifts, ensures a reasonable time between IN shifts, and balances the types of ON shifts across the board.

This is no simple task and it can often take hours to iron out all the inefficiencies in the resulting schedule. Additionally, it is somewhat worrisome that the RAs creating the schedule are responsible also for scheduling themselves, a potential conflict of interest.

But worry not!

This problem, creating an optimal schedule subject to many hard, and some softer constraints, belongs nicely to a family of problems called Constraint Satisfaction Problems (CSPs) which computers are really really good at solving fast.

The only challenge for us is to take this very human problem, and translate it into a problem that a computer can understand and then solve. If you think this sounds crazy complicated, don’t worry. I promise it will be much easier than you think. Let’s get started!

What are the Variables?

In order to translate this scheduling problem into something a computer can solve, we need to figure out what our variables are going to be. At first thought, this seems to be too broad of a problem. Should we think about how many shifts each RA gets? Should we try and use the number of days between shifts as our variables? How about the order of the shifts by RA?

In fact, the choice of variables is even more basic and will implicitly be able to take all these questions into account. Given some number of RAs in the building, let’s say 24 for now, and some number of days to schedule, let’s say 27 days, we will define:

\[ON_{i,j} = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 1 & \text{if RA i scheduled ON for day j} \\ 0 & \text{if not} \\ \end{array} \right .\]and

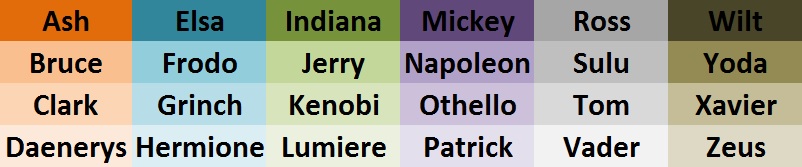

\[IN_{i,j} = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 1 & \text{if RA i scheduled IN for day j} \\ 0 & \text{if not} \\ \end{array} \right .\]So, assume we have the following list of 24 RAs

and we want to schedule them for the 27 day period Sunday May 15th 2016 - Friday June 10th 2016.

If we know that

\[ON_{Bruce, Jun 1} = 1 \text{ and } IN_{Clark, Jun 1} = 0\]then we know that Bruce is ON duty on the night of June 1st and Clark is not IN duty on the night of June 1st.

How many of these variables are there? Well there are 24 possibilities for the RA and 27 possibilities for the day so we get a total of 24 times 27 or 648 variables. Whoa! I thought we said this would be simple! Don’t stress, it will be, and it’s all because these variables, as many of them as we have, can only be 0 or 1, which is the key structure we will take advantage of when formulating our problem. Let’s turn our attention to the different kinds of constraints we have for these variables.

Rules for Scheduling

There are a couple of hard constraints when we try and solve this scheduling problem. Let’s define what this means.

Hard Constraint: A rule that, if violated, makes for an invalid schedule

Let’s go through each constraint and see how a human would state it and how we can express it with our variables.

Sufficient Staff Constraint

Hard Constraint 1: We need exactly three RAs with ON shifts and three RAs with IN shifts each night

Hmm … how do we express this with our variables? Well, starting simple, we can choose a day, say May 15th. We know that exactly (no more, no less) three RAs need to have ON shifts on May 15th. How do we count how many people will be ON for May 15th? Well since $ON_{i, May 15} = 1$ if RA $i$ is ON and $0$ if not, all we need to do is sum up the May 15 variable for all the RAs:

\[ON_{Ash, May 15} + ON_{Bruce, May 15} + ... + ON_{Xavier, May 15} + ON_{Zeus, May 15}\]and that will tell us how many RAs have ON shifts for May 15th.

For some proposed schedule, if the sum is 2, we reject that schedule since not enough RAs are staffed ON that night. If that sum is 4, we also reject that schedule since too many RAs are staffed ON that night. We need it to be exactly 3. So we need

\[ON_{Ash, May 15} + ON_{Bruce, May 15} + ... + ON_{Xavier, May 15} + ON_{Zeus, May 15} = 3\]and similarly,

\[IN_{Ash, May 15} + IN_{Bruce, May 15} + ... + IN_{Xavier, May 15} + IN_{Zeus, May 15} = 3.\]But, we can just do this for each of the 27 days since we have the same constraint every night. So, in a nutshell

\[ON_{Ash, j} + ON_{Bruce, j} + ... + ON_{Xavier, j} + ON_{Zeus, j} = 3\]and

\[IN_{Ash, j} + IN_{Bruce, j} + ... + IN_{Xavier, j} + IN_{Zeus, j} = 3\]where $j$ is each day from May 15th to June 10th.

Cool, that was pretty painless, and now we have our first constraint. Let’s press on!

Equal Work Constraint

Let’s do a quick calculation of roughly how many ON shifts each RA should have in this time period. There are 27 days with 3 ON shifts per day for a total of 81 ON shifts spread across 24 RAs for a total of 3.375 ON shifts per RA. Well, we can’t give partial ON shifts to an RA, so we want that each RA has either 3 or 4 ON shifts. The same holds for IN shifts.

Hard Constraint 2: Each RA has either 3 or 4 ON shifts and either 3 or 4 IN shifts

We could imagine that even with this constraint, Bruce, for example, might get lucky with 3 ON and 3 IN duties and Clark might get very unlucky with 4 ON and 4 IN constraints. This seems a bit unfair so we want the total number of duties (ON + IN) for each RA to be either 7 or 8. This is basically saying that no RA should get away with having 3 ON shifts and 3 IN shifts.

Hard Constraint 3: Each RA has either 7 or 8 total shifts

Now, how do we translate these using our variables? The number of total ON shifts any given RA has is calculated by adding up their \(ON\) variables (which is 1 if they have an ON shift on a given day and 0 if not) for 27 days. For example, if we want to know how many ON shifts Vader has for the 27 day period, we need to sum:

\[ON_{Vader, May 15} + ON_{Vader, May 16} + ... + ON_{Vader, Jun 9} + ON_{Vader, Jun 10}\]and ensure that this sum is either 3 or 4. We do the same for IN shifts.

To satisfy Hard Constraint 3, we need only do ensure that:

\[7 \le (ON_{Vader, May 15} + IN_{Vader, May 15}) + ... + (ON_{Vader, Jun 10} + IN_{Vader, Jun 10}) \le 8.\]Burnout Constraint

Even if we assure that two RAs have the same number of ON shifts, let’s say three each, we say nothing about how those shifts are spread out. For example, if Clark has three ON shifts on May 15, May 30, and June 10, he enjoys a relatively spread out workload. If Bruce, on the other hand, has three ON shifts on May 15, May 16, and May 17, he faces three continuous days of work and has a much greater stress level. We thus want the following three hard constraints:

Hard Constraint 4: Each RA has at least 7 days between ON shifts

Hard Constraint 5: Each RA has at least 7 days between IN shifts

Hard Constraint 6: Each RA has at least 2 days between an ON shift and an IN shift

You’re probably asking, where did these numbers come from? For a specific instance of this problem, with some historical shift preference data, I found that these were the highest numbers that still resulted in a valid schedule. For this reason, the fine tuning of these numbers is built into the model and it will keep trying to build schedules until it maximizes each of these three numbers. More on this later on.

The question for now is how to express these constraints using our variables. It seems a bit difficult at first since our variables only tell us whether or not an RA is working on a given day, not the time between shifts. But, we can be a little creative here. Let’s start simple.

Let’s say we want to enforce Hard Constraint 4 for Elsa. We know that for the first seven days of the scheduling period, May 15 - May 21, she can have at most one ON shift. If she had two or more, then these shifts would be less than 7 days apart and we would be violating the constraint. So we need:

\[ON_{Elsa, May 15} + ON_{Elsa, May 16} + ... + ON_{Elsa, May 20} + ON_{Elsa, May 21} \le 1\]Then, if we move this seven day window forward by 1, to get the range May 16 - May 22, we know that she can also have at most one ON shift in this range, for the same reason as before.

\[ON_{Elsa, May 16} + ON_{Elsa, May 17} + ... + ON_{Elsa, May 21} + ON_{Elsa, May 22} \le 1\]We just keep rolling this seven day window through the full 27 days and set the same less than or equal to 1 ON shift constraint for each window.

This can be confusing with just words so let’s see some pics. The first window looks like this:

Then we add another day to the end of the window and remove one from the beginning:

And then continue …

We make sure that in each seven day window, each RA has no more than one ON shift.

We do the analysis for IN shifts in the same way since Hard Constraint 5 requires also 7 days. To meet Hard Constraint 6, we need to make sure that the sum of all the $ON$ and $IN$ variables for each RA for each two day window is no more than 1. For example, for Elsa, we need that:

\[(ON_{Elsa, May 15} + IN_{Elsa, May 15}) + (ON_{Elsa, May 16} + IN_{Elsa, May 16}) \le 1\] \[(ON_{Elsa, May 16} + IN_{Elsa, May 16}) + (ON_{Elsa, May 17} + IN_{Elsa, May 17}) \le 1\] \[...\] \[(ON_{Elsa, Jun 9} + IN_{Elsa, Jun 9}) + (ON_{Elsa, Jun 10} + IN_{Elsa, Jun 10}) \le 1\]Serendipitous Sidenote

Even though it is evident to a human that we cannot assign the same person for two different shifts in a given day, the computer will not know that unless we state it as a constraint. We have “accidentally” set this constraint implicit in Hard Constraints 4 through 6. For example, if we propose a schedule where Elsa is scheduled to be ON and IN for June 10, we will have that

\[(ON_{Elsa, Jun 9} + IN_{Elsa, Jun 9}) + (ON_{Elsa, Jun 10} + IN_{Elsa, Jun 10}) = 2\]which violates the final constraint in the preceding section.

Preference Constraints

So far, we have only encoded constraints that are globally applicable across all RAs. But, as we said before, RAs submit preferences about which shifts they would like to have on each day. These preferences are as follows:

ON Preference: I would prefer to have an ON shift this day

IN Preference: I would prefer to have an IN shift this day but if not, do NOT schedule me to work this day at all

OFF Preference: Do NOT schedule me for work this day

NO Preference: Anything you assign to me this day is fine

We care right now about the IN and OFF Preferences, which give rise to our two last Hard Constraints.

Hard Constraint 7: Never schedule someone for an ON shift if they put an IN preference

Hard Constraint 8: Never schedule someone for an ON or IN shift if they put an OFF preference

These are pretty simple to encode. For example, if Yoda put an IN Preference on May 15, we simply need that:

\[ON_{Yoda, May 15} = 0.\]And if Patrick had put an OFF preference on June 10, we simply need that:

\[ON_{Patrick, Jun 10} = 0\] \[IN_{Patrick, Jun 10} = 0.\]And with that, we have all our Hard Constraints. Any proposed schedule that meets all eight of these Hard Constraints is a perfectly acceptable schedule and we can use it for the next 27 days.

Picking the Best of the Best

But, there are probably many such perfectly acceptable schedules and we want to be a bit picky. We want to pick the one which maximizes some value which is linked to how many ON Preference and IN Preferences we satisfy. That is, out of all the acceptable schedules, we want to pick the one which gives the most RAs their preferred choice of shift across the 27 days.

We encode this preference through a Soft Constraint, defined below.

Soft Constraint: A rule that says how to pick the best schedule out of all acceptable ones

We want this rule to be some function of how many times we match up an ON preference with an ON shift and how many times we match up an IN preference with an IN shift across all RAs and all days. To make this a bit easier, we will define a new measure for each RA as follows:

\[A_{i} = \text{Number of ON shifts for RA $i$ which s/he had put an ON preference for}\] \[B_{i} = \text{Number of IN shifts for RA $i$ which s/he had put an IN preference for}\]Given these two new measures, we can define the following measure, $K$:

\[K = (A_{Ash} + A_{Bruce} + ... + A_{Zeus}) + (B_{Ash} + B_{Bruce} + ... + B_{Zeus})\]What does this measure? This sum tells us how many total shift preference matches there were for an acceptable schedule across all RAs and all 27 days.

Let’s make one slight modification to this function before we define our Soft Constraint. In the above function we are weighting matches for ON shifts the same as matches for IN shifts. But, in reality, we would value a match for an ON shift more than one for an IN shift. This is because matching an ON shift alleviates some stress by virtue of having the shift on a more ideal day. We will thus use the following modified measure, $K’$:

\[K' = 2 \times (A_{Ash} + A_{Bruce} + ... + A_{Zeus}) + (B_{Ash} + B_{Bruce} + ... + B_{Zeus})\]This effectively puts double the weight on matches for ON shifts than matches for IN shifts and these weights can be modified according to situation.

We thus specify our single Soft Constraint.

Soft Constraint 1: Out of all acceptable schedules, pick the one with the highest value for $K’$

Let’s take a step back and go over what we have done.

1. We start by enforcing universal constraints which need to be satisfied for a valid schedule

2. We then look at the list of preferences by each RA for which shifts they want on which day

3. Of these constraints, we enforce those which disqualify certain RAs from working certain shifts on certain days

4. Given all these constraints, we have multiple schedules which all are perfectly acceptable

5. Wanting to do even better, we pick from these acceptable schedules the one which maximizes a measure of matching between preferences and assigned shifts, with a higher weight on matching ON shifts

In the end, we hopefully have a fully optimized schedule. We say hopefully because it is possible that given some RA preferences, an optimal schedule might not be possible. In an extreme case, assume that there is some big festival on June 4 and 21 of the 26 RAs have put OFF preference for that day. This leaves only 5 RAs who can work that day, not enough to fill the three ON shifts and three IN shifts that day. These cases will likely not occur, but if they do, staff members must work out a solution before turning again to the scheduling algorithm.

Varying Shift Types

A keen reader will notice that at the beginning of the post, it was stated that we also want to have an even spread between the different types of ON shifts, ON 1, ON 2, and ON 3, since these shifts patrol different areas of the building. Currently this is nowhere in our scheduling method. This is mainly because it can be done independently of all other constraints. Since RAs list preferences only for wanting an ON shift and not for which particular ON shift, and because permuting the three different ON shifts between three RAs in a given day cannot violate any Hard Constraints, we are safe to assign the particular ON shift after picking an optimal schedule.

The question is then how we will go about evening out the different ON shifts across all RAs. We will use a greedy approach where we go day by day in the optimal schedule and give a particular ON shift to the person who most needs it of those scheduled ON that day.

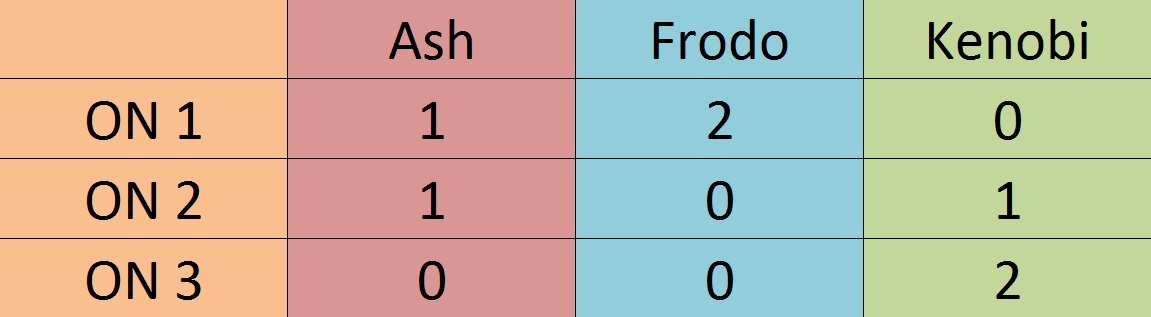

Let’s make this more concrete with an example. Suppose we have distributed the various types of ON shifts for May 15 through June 6 and are now looking to distribute the three types of ON shifts to those scheduled ON for June 7. Suppose the three RAs scheduled ON for June 7 are Ash, Frodo, and Kenobi. And suppose the number of ON shift types so far is as follows:

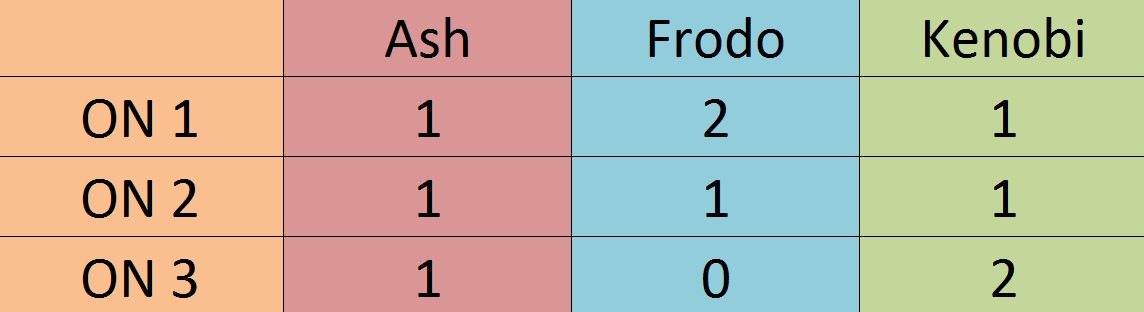

We see that there is an imbalance, especially since Frodo has only ON 1 shifts. To try and choose the best assignment of ON shifts for June 7, we will first calculate the target number of ON shifts by type for each RA. This is simply done by taking the total number of ON shifts for that RA so far and dividing by 3, the number of types of ON shifts. This gives us the following table.

This tells us, for example, that Kenobi should ideally have 1 ON shift of each type and that Ash and Frodo should ideally have 0.667 ON shifts of each type, which is of course impossible, but gives us our target for an equal allocation.

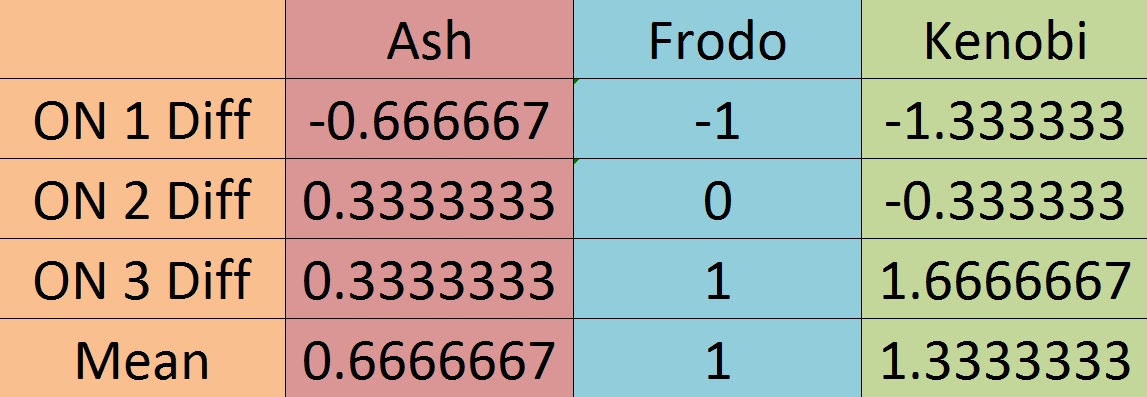

Now, we will calculate the difference of each type of ON shift for each of these three RAs from their target number. For example, Kenobi should have 1 of each type and in reality he has zero ON 1 shifts so the difference is 0 - 1 = -1. We see the rest of the numbers below:

We are really interested in which ON shift types have the lowest numbers for each RA, shown below.

The boldface numbers tell us which of the three types of ON shifts each RA is really lacking, since they are the ones most below the target values. This tells us which shifts to prioritize when deciding what to assign. We will start with the RA most in need, indicated by the lowest of all boldfaced numbers. This is Kenobi, with a -1 for his ON 1 shifts. We will assign ON 1 for June 7 to Kenobi. We then see that the rest of the boldfaced numbers are all of the same magnitude so we will randomly assign between the other two shifts. In the end, our updated ON shifts per RA looks like this.

We see that we are getting a lot closer to a fully balanced distribution. Note that even though it is less important which IN shifts (IN 1, IN 2, IN 3) RAs get assigned to since the roles are not really different, we still perform the same equal distribution analysis for IN shifts since it is not very computationally expensive.

A More Extreme Case

For example’s sake, let’s pretend that we are trying to decide what to assign for a day when the difference table looks like this.

We see that all three RAs really need an ON 1 shift, but we give it to Kenobi since the number is the lowest. We then give Frodo an ON 2 shift since that is the next best shift we can assign to him. We are then forced to give Ash the ON 3 shift even though it doesn’t really help his distribution. But since Ash’s distribution is now more uneven, when it comes time to again assign him a shift, his difference numbers will indicate a greater need for an ON 1 shift than other RAs.

Looking Back to Optimize Forward

Let’s say we use our schedule for the first 27 days of the year and get a nice optimized schedule as balanced as possible. We say “as possible” since there are some things that just cannot be perfectly balanced. A prime example is the number of ON shifts per RA. We said that we can get the difference in ON shifts down to 1, but we physically cannot assign every RA the same number of ON shifts because we cannot have fractional shifts.

Now, let’s say that at the end of our 27 days, we want to make a schedule for another 27 days. If we ignore the past and pretend like we are starting fresh, we will definitely introduce biases and inequalities for some RAs. Take the following case. Assume Mickey was assigned 4 ON shifts in the first scheduling period, while Ross was assigned only 3. This is acceptable since we allow the number of ON shifts to be off by one. It would be unfair though if in the second scheduling period, we again assigned Mickey 4 ON shifts and Ross 3 ON shifts.

It is thus very important to keep some record of the past including how many ON shifts each RA has going into a new scheduling period, how many IN shifts they have, and what kind of ON shifts they have. We can use this history to correct for previously inevitable inequalities.

Let’s See Some Results

Whew! That was a lot of work. Hopefully it was all worth it and we can build nice evenly spread out schedules for the RAs. Let’s try and build a schedule for four weeks using some historical preference data. First a quick note.

Note

Remember our Hard Constraints about the time between ON and IN shifts? For our example we picked 7 days between ON shifts, 7 days between IN shifts, and 2 days between an ON and IN shift. IN reality, this will not always be possible and we will have to reduce the number of days between shifts to get a valid schedule.

How the scheduler works is by starting very optimistic and setting the time between ON and IN shifts to 7 as well as setting the time between an ON and IN shift to 7. If it succeeds in building a valid schedule with those constraints, it is done. If it cannot build one, it reduces all three numbers by 1, so we are at 6 days between each kind of shift. It continues until it finds a triple where a valid schedule can be build.

Let’s say that triple is (2,2,2) so that the schedule has 2 days between ON shifts, 2 days between IN shifts, and 2 days between ON and IN shifts. It then boosts the time between ON shifts as much as possible and then does the same for the time between in shifts so the final triple might look something like (7,5,2) where the time between ON shifts is 7, time between IN shifts is 5, and the time between an ON and IN shift is 2.

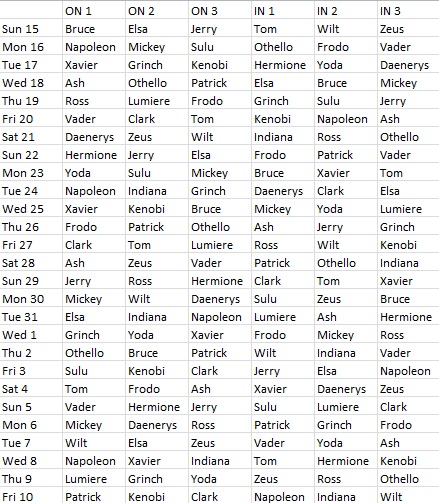

Four Week Schedule

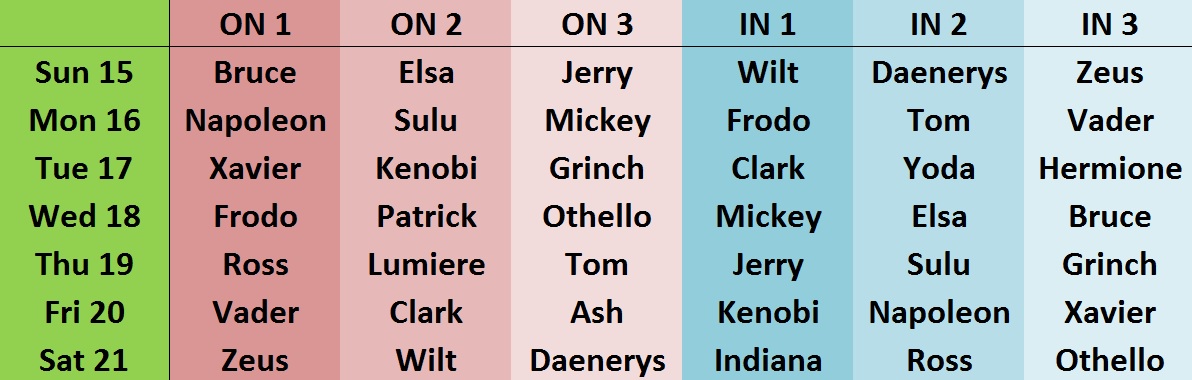

Let’s see the results of scheduling four weeks.

We can’t really decipher much by looking at it overall, so let’s focus on two RAs and see how well we scheduled them.

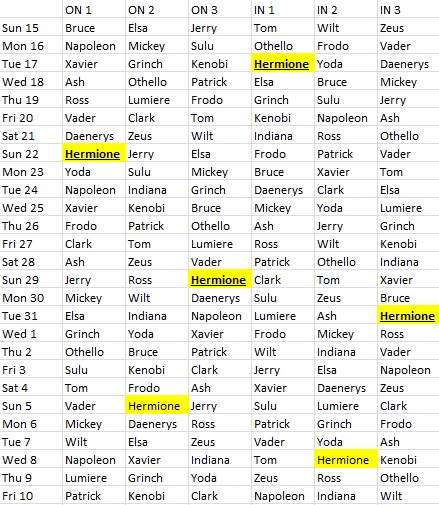

Let’s first look at Hermione. Her shifts are highlighted in yellow and the ones where we matched her preference to her actual shift are bolded and underlined.

Her shifts look fairly spread out and we were even able to match four of her six shifts to her preferences. Also, she was assigned one of each type of ON shift and one of each type of IN shift, a perfect spread!

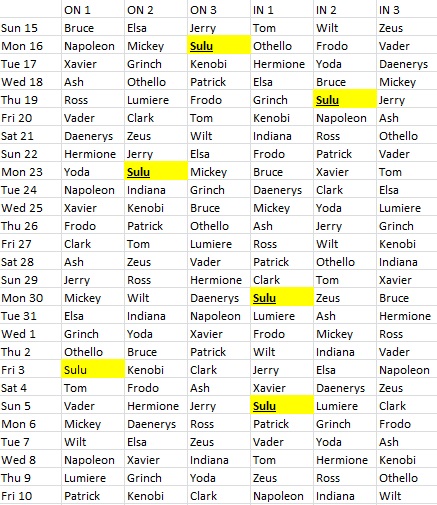

Lets look at the same schedule for Sulu.

Sulu’s schedule looks pretty good too but we might be worried that its bunched up more than Hermione’s is. When we look at the preferences data though, we see that Sulu listed an OFF preference for each day from June 6 - June 10, so the scheduling procedure did its best given that it was effectively trying to schedule the same amount of shifts for Sulu with five less days. Still, we were able to give Sulu one of each type of ON shift. Furthermore, we matched five of his six shifts to his preferences!

So How Fast Is It?

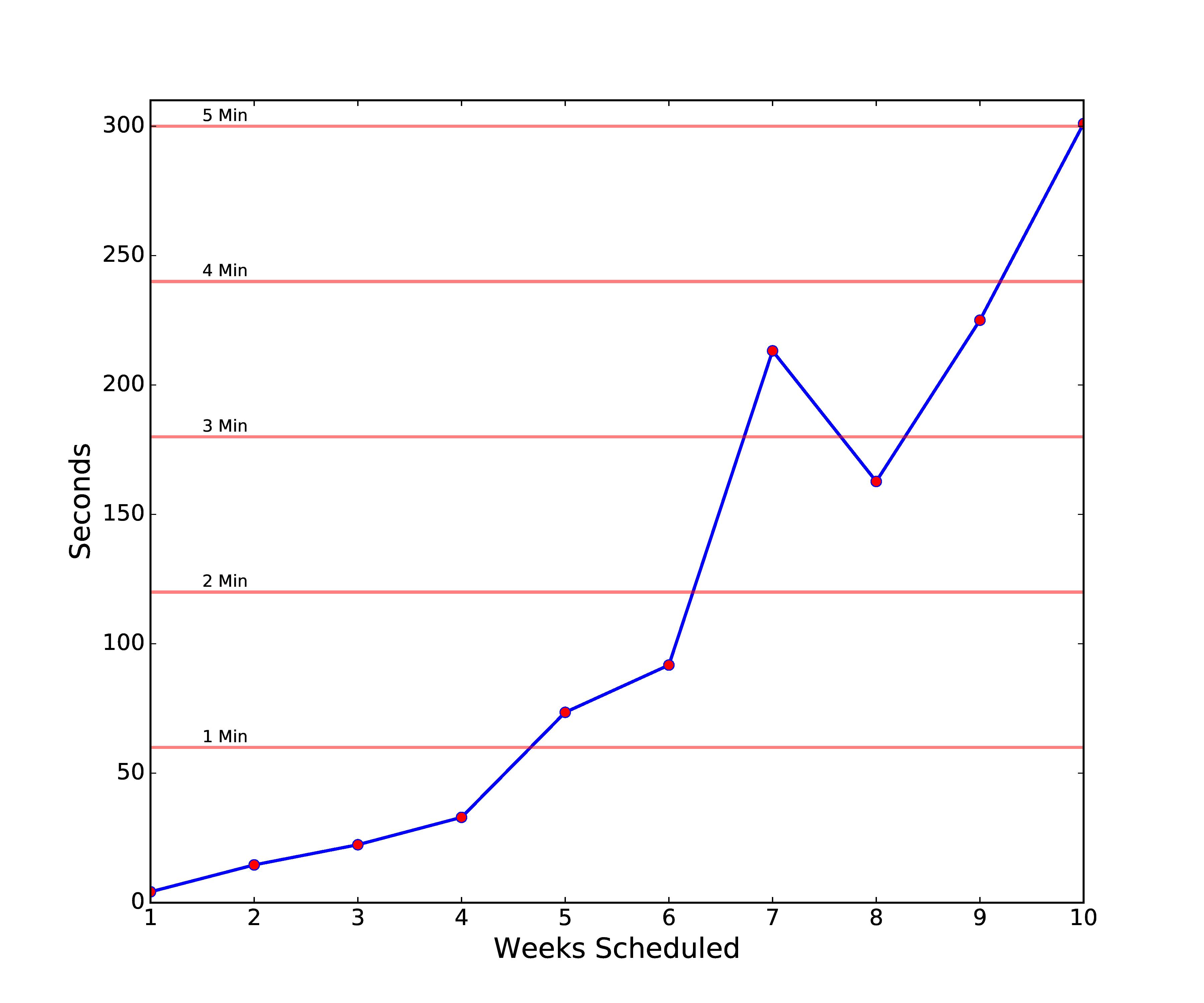

The burning question for many of you is probably “How fast is all this?” This is a great question since our main motivation for doing all this was to improve upon the speed and accuracy of the current by-hand process. We have seen that we are doing pretty well in the accuracy department mainly because of our Hard Constraints and optimization via our Soft Constraint. As for speed, this graph tells it all.

Wow! Even if we are trying to schedule the entire 10 week quarter at once, we can get results in about 5 minutes. In the more likely case, where we are scheduling 3 to 4 weeks at a time, we get our results in under a minute. It’s around the 7 week mark where the time really starts to shoot upwards as the problem gets harder to solve. It seems we have achieved our goal!

Why the Dip?

We expect that as we schedule more weeks, the time the scheduler takes will go up so it might seem a bit odd that we have the dip between 7 and 8 weeks. It can be possibly explained as follows. Suppose we are trying to schedule one week and half our RAs have mainly put OFF preferences, making it really hard to schedule them in. Thus, it takes a long time to schedule. Now let’s say we are trying to schedule two weeks, where in the second week the problematic RAs are very free. This makes it a lot easier to build an overall two week schedule and solves some of the issues with scheduling just one week. So in a nutshell, it’s a symptom of the preferences and might change with different preferences.

How Do I Use It?

The scheduler is freely available in the SADIE folder on my GitHub, linked at the bottom of this page. SADIE stands for Scheduling All Duties Incredibly Efficiently. Here are the steps to building optimal schedules for your own company / staff / organization.

Getting Worker Preferences

- From my GitHub download a file called example_preferences.csv

- This file shows how the scheduler wants the preferences to look. The time period in this example document is the same we have used through this post for convenience

- You need to replace the names with your own worker’s names and change the date range to what you prefer. You should add / remove weeks if needed

- Workers should put one of four things in each cell corresponding to their name. They can put:

- ‘ON PREF’: Please try and schedule me ON that day

- ‘IN PREF’: Please try and schedule me IN that day but do NOT schedule me ON

- ‘OFF’: Do NOT schedule me that day

- blank: No preference, anything is fine

- Please keep the preferences in csv format and rename the file to whatever name you prefer

Making the Optimal Schedule

- From my GitHub download a file called SADIE.exe

- Put SADIE.exe in the same folder as your preferences csv document

- Run SADIE.exe

- SADIE will ask you some questions including:

- What day you want to start scheduling

- How many days you want to schedule

- How many ON / IN shifts there should be per day

- SADIE will then run for a while depending on how strict the preferences are and how many weeks you are trying to schedule

- Once SADIE is done, you will have a file called duty_sched.csv in the same folder that SADIE.exe is in

- duty_sched.csv contains the optimized shift schedule

- There is a chance that, if your staff’s preferences make for an impossible schedule, SADIE will inform you that there is no possible schedule, in which case you will need to change the preferences csv file and try again

For Second, Third, etc. Scheduling Periods

It is totally up to you how much of SADIE’s suggestions about optimal schedule you use. But, when you want to run SADIE again after a few weeks, it needs to know what the previous shift assignments were so that it can use that past to optimize the future. Follow these steps for a second, third, etc. scheduling run.

- In your preferences csv document include ALL dates from the beginning of the quarter / year / term until the last date you are trying to schedule. Eg. If you scheduled May 15 - Jun 10 and now you want to schedule Jun 11 - Jun 30, include all days from May 15 - Jun 30.

- For the dates that have already been scheduled (eg. May 15 - Jun 10), put ‘ON 1’, ‘ON 2’, etc. for the workers who have been assigned to those shifts on each day. Same goes for putting in ‘IN 1’, ‘IN 2’, etc.

- It is OK to leave ‘ON PREF’, ‘IN PREF’, ‘OFF’ in the past dates

- For the dates you are trying to schedule (eg. Jun 11 - Jun 30), you just need to make sure all workers have put ‘ON PREF’, ‘IN PREF’, ‘OFF’

- Run SADIE as usual, making sure to input the start schedule date and number of days to schedule properly

Thanks for Reading and Leave Comments!