What is the Probability that a God Exists?

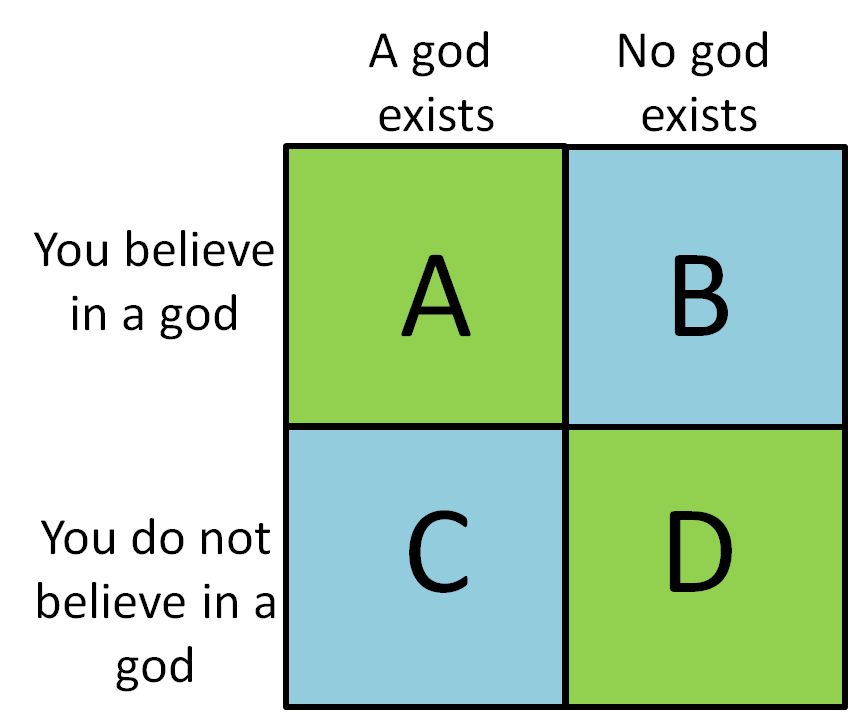

As seventeenth-century mathematician, philosopher, and physicist Blaise Pascal described, there are only four possible states of the universe:

\[\textrm{Case A: You believe in a god and this god exists }\] \[\textrm{Case B: You believe in a god but no god exists}\] \[\textrm{Case C: You do not believe in any god but a god exists }\] \[\textrm{Case D: You do not believe in any god and no god exists}\]Each case has an associated benefit (Case A and Case D) or cost (Case B and Case C). For example, in case A, you should be rewarded for your belief through some beneficial afterlife, or constructive reincarnation, etc. But, for example in case C, you might suffer a terrible fate after death or a similarly grave outcome. We can enumerate the benefits and costs in a payoff matrix:

where

\[A = \textrm{Benefit from believing in a god when a god exists}\] \[B = \textrm{Loss from believing in a god when no god exists}\] \[C = \textrm{Loss from not believing in a god when a god exists}\] \[D = \textrm{Benefit from not believing in a god when no god exists}\]We assume that

\[A > 0, B < 0, C < 0, D > 0\]since you being right about the existence/non-existence of a god is a gain while you being wrong about the existence/non-existence of a god is a loss.

We will also assume that each person has their own personal probability, $ p $, that a god exists. This is really a measure of your faith in the existence of a god:

\[p = \textrm{Your Personal Probability That a God Exists}\]Now what is your expected payoff if you choose to believe in a god? Well it should be a probability-weighted average of your reward in the case where you believe in a god and a god exists (Case A) and your loss in the case where you believe in a god but no god exists (Case B). In other words:

\[\textrm{Expected Payoff from Belief} = p \times A + (1-p) \times B\]Similarly,

\[\textrm{Expected Payoff from Disbelief} = p \times C + (1-p) \times D\]Now, assuming that you believe in a god, it should be the case that:

\[\textrm{Expected Payoff from Belief} > \textrm{Expected Payoff from Disbelief}\]otherwise you would choose disbelief over belief.

In other words:

\[p \times A + (1-p) \times B > p \times C + (1-p) \times D\]which simplifies down to:

\[p > \frac{(D-B)}{(D-B) + (A-C)}\]But what is $(D-B)$? It is really the added benefit you get from switching from belief to disbelief in a world where there is no god. Let’s say $G_{disbelief} = D-B$.

And what is $(A-C)$? It’s just the added benefit you get from switching from disbelief to belief in a world where there is a god. Let’s say $G_{belief} = A-C$.

So, if you choose to believe in a god:

\[p > \frac{G_{disbelief}}{G_{disbelief} + G_{belief}}\]Let’s define $Q$ as

\[Q(G_{belief}, G_{disbelief}) = \frac{G_{disbelief}}{G_{disbelief} + G_{belief}}\]so

- if $p > Q(G_{belief}, G_{disbelief})$, you choose to believe in a god

- if $p < Q(G_{belief}, G_{disbelief})$, you choose to not believe in a god.

What happens if $G_{belief}$, your gain from believing in a god, gets higher and higher? Well, $Q$ will approach $0$ and you will choose to believe in a god even if your personal probability that a god exists, $p$, is small. In more casual terms,

If you think your life will be a lot better by believing in a god, you don’t necessarily need great faith in the existence of a god to believe

Let’s flip that story. If $G_{disbelief}$, your gain from not believing in a god, gets higher and higher, the quantity $Q$ will approach $1$. In everyday terms this says that

If you think your life will be a lot better by not believing in a god, you would need a lot of faith in the existence of a god to believe

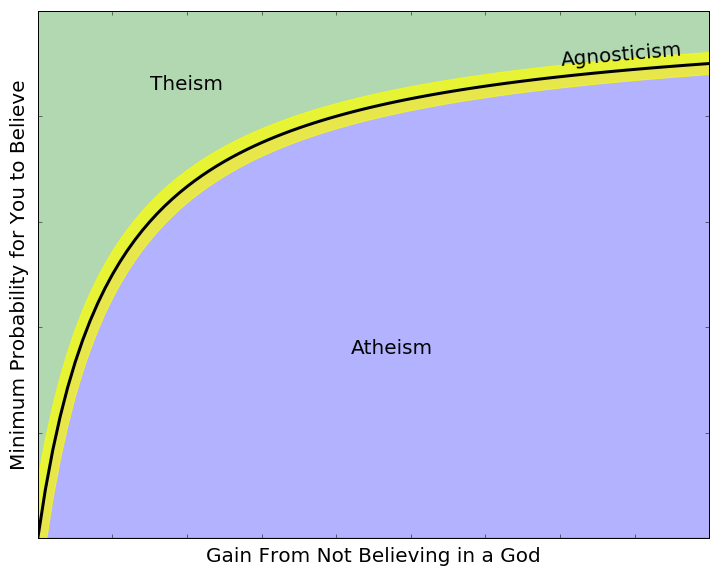

Enough equations for a bit, let’s see some graphs that help us see this a bit better.

To see what happens when your belief in a god grows, let us fix $G_{disbelief} = 1$ and see what happens to $Q$ as $G_{belief}$, your gain from believing in a god when a god exists, grows.

-

We see that as your gain from believing in a god grows, perhaps due to life experiences fostering belief or the support of a close community of believers, you don’t need as much faith to believe. Mathematically, your minimum probability threshold approaches 0.

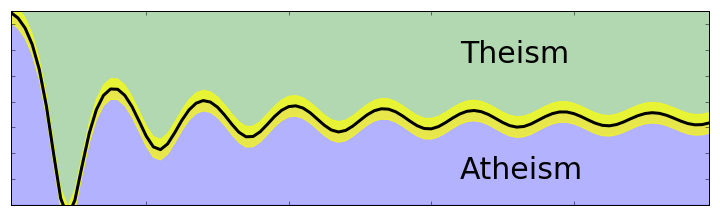

-

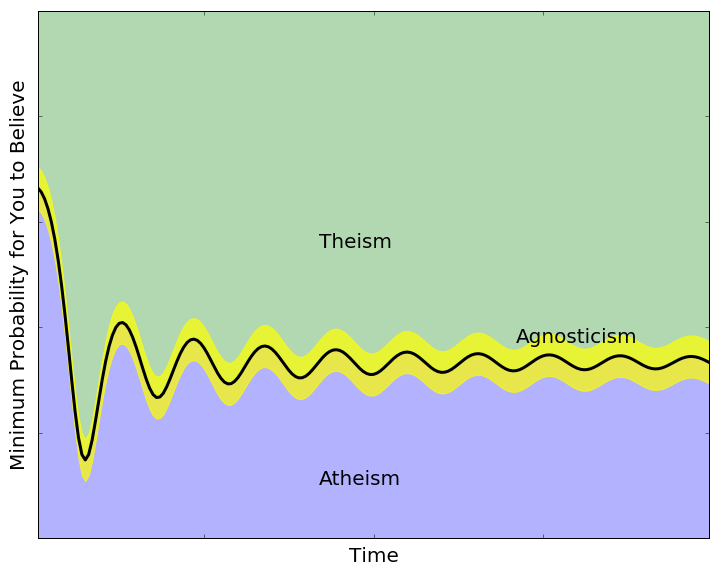

We see that anyone whose level of faith is below the minimum threshold would be an atheist, choosing not to believe in god. Anyone whose level of faith is above the threshold would be theist, choosing to believe in a god. And, interestingly, anyone whose level of faith is at or very close to the threshold would be agnostic, perhaps unsure of the existence of a god.

Now for the flip side of that story. What happens if we fix $G_{belief} = 1$ and see what happens as we let $G_{disbelief}$, your gain from not believing in a god when no god exists, grow to higher and higher values?

- We see that as your gain from not believing in a god grows, maybe due to losing touch with religion or substituting religion for other ideals, you need more and more faith to believe in a god. Mathematically, your minimum probability threshold approaches 1.

Cool! Let’s close by extending our model a bit to capture a bit more of reality. In truth, faith in the existence of a god is a function of time. Maybe you were raised very religiously but later in life, abandoned those ideals. Or perhaps, you were raised in a very secular household, but later found solace in the idea of religion.

In the same way, your personal costs and benefits from believing or not believing in a god change over time as well. Perhaps your gain from believing in a god rises over time as you find support from a close group of believing individuals. Or perhaps your gain from not believing in a god rises as you mingle with those who choose to not believe in any god. Maybe it’s even a combination of both!

Let’s consider a concreate example. Suppose $t$ represents time. Let’s say that

\[G_{belief} = 2t\]so that your gain from believing in a god rises over time. Let’s also say that

\[G_{disbelief} = t + sin(3t)\]so that your gain from not believing in a god rises over time in general (as a result of the first $t$ term) but that it also fluctuates up and down a bit over time (as a result of the sine function).

Then, returning to our framework built above:

\[Q(t) = \frac{G_{disbelief}}{G_{disbelief} + G_{belief}} = \frac{t + sin(3t)}{2t + t + sin(3t)}\]What happens as you get older (i.e. as $t$ approaches larger and larger values)?

Well, the sine term is bounded between -1 and 1 so it ceases to be a significant factor for large values of $t$.

Over time,

\[Q(t) \rightarrow \frac{t}{2t + t} = \frac{1}{3}.\]Wow! So, over time, your minimum faith threshold approaches neither 0 nor 1, but $\frac{1}{3}$. That is, as you get older and older, if your personal probability that a god exists exceeds $\frac{1}{3}$, you will choose to believe in a god. Otherwise, you will choose to not believe.

Furthermore, this threshold is much more volatile early in your life and stabilizes later on, as you age.

Let’s see a graph:

Let’s take a final step by saying that your personal probability $p$, that a god exists starts at $p=1$ when you are young ($t=0$) and decreases over time according to the function:

\[p(t) = 1 - t\]Assuming $t=1$ is the end of your life, we find that setting

\[p(t) = Q(t)\]gives

\[1 - t = \frac{t + sin(3t)}{2t + t + sin(3t)}\]which is satisfied when $t = 0.37$. That is,

\[\textrm{if } t < 0.37, \textrm{ we have that } p(t) > Q(t)\] \[\textrm{if } t > 0.37, \textrm{ we have that } p(t) < Q(t)\]So, for about the first third of your life, you believe in a god since your personal probability $p(t)$ is above the threshold, $Q(t)$ but for final two thirds of your life, this story reverses so that you no longer believe in a god.

We can try a lot of different functions of time for $G_{disbelief}$ and $G_{belief}$ and $p(t)$! The possibilities for exploring this model are endless!